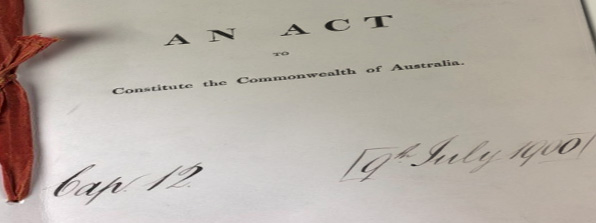

The latest constitutional bugbear and High Court headache is whether or not some holders of public office are eligible to hold on to their positions given their dual citizenship status – regardless of whether they were in fact aware of their status prior to their entry into the Parliament.

Unfortunately, the relevant section of the Constitution, section 44 is as ambiguous as it is anachronistic and reads as a whole as follows:

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA CONSTITUTION ACT – SECT 44

Disqualification

Any person who:

(i) is under any acknowledgment of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, or is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or a citizen of a foreign power; or

(ii) is attainted of treason, or has been convicted and is under sentence, or subject to be sentenced, for any offence punishable under the law of the Commonwealth or of a State by imprisonment for one year or longer; or

(iii) is an undischarged bankrupt or insolvent; or

(iv) holds any office of profit under the Crown, or any pension payable during the pleasure of the Crown out of any of the revenues of the Commonwealth; or

(v) has any direct or indirect pecuniary interest in any agreement with the Public Service of the Commonwealth otherwise than as a member and in common with the other members of an incorporated company consisting of more than twenty-five persons;

shall be incapable of being chosen or of sitting as a senator or a member of the House of Representatives.

But subsection (iv) does not apply to the office of any of the Queen’s Ministers of State for the Commonwealth, or of any of the Queen’s Ministers for a State, or to the receipt of pay, half pay, or a pension, by any person as an officer or member of the Queen’s navy or army, or to the receipt of pay as an officer or member of the naval or military forces of the Commonwealth by any person whose services are not wholly employed by the Commonwealth.

Leaving aside s44 (ii-v) which has no direct bearing on the current bruhaha, section 44(i) is the portion that has the parliament very concerned and that has led to a raft of referrals of its members to the High Court for determination as to their eligibility to in fact sit in its chambers.

Section 44(i) is itself further broken down into three distinct branches; namely, a person is disqualified from being a parliamentarian if:

- is under any acknowledgment of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, OR

- is a subject or a citizen [of a foreign power], OR

- entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or a citizen of a foreign power.

The first ‘branch’ is reasonably straight forward and unambiguous, given that if a person has a declared and willing acknowledgment of loyalty, obedience or adherence to a foreign power, then, they cannot be a member of the parliament – end of story.

The third ‘branch’, thankfully is not the salient question being challenged as no-one really knows what this part really entails and may include the obvious, such as a passport and the less obvious, such as a foreign age pension, or even a train concession card or free medical care (given that often such privileges are not only available to citizens but are obviously rights and privileges of citizens).

The second ‘branch’ on the other hand is the troublesome one as it relies on the definition of ‘citizen’ and ‘subject’ which, has in fact nothing to do with the laws of Australia, but rather what a ‘foreign power’ deems a ‘citizen’ or a ‘subject’ to be.

Therefore, the deciding factor as to whether quite a few politicians will be looking for a new occupation, is likely to be a determination of the semantics of the words ‘citizen’ and ‘subject’ and whether the unknown acquisition of a dual nationality is ground for disqualification from the holding of public office.

Whereas the first branch of 44(i) clearly puts a positive obligation to a person to have in fact ‘done something’ to pledge allegiance to a foreign power, clearly a red card, being a subject or a citizen of a foreign power may in fact be eventually determined to be a distinction or exception to the disqualification rule, given that it relies solely on the laws of the foreign power itself without any input from the person impacted by the burden; particularly in the instance of the word ‘subject’ which, the Oxford Dictionary defines as:

‘A member of a state other than its ruler, especially one owing allegiance to a monarch or other supreme ruler’.

Without verballing the High Court in its absolute wisdom, the likely solution to this problem will possibly lie with the re-definition of the words Citizen and/or Subject to allow for these to be in fact determined by Australian Law rather than the laws of essentially every individual country, state and territory on earth.

If I were a betting man, I would put some money on the High Court finding a way out of this shemozzle and allowing our good politicians to continue their essential good work – which by the way, will make a few naïve Green senators regret their impetuous decisions to resign at the first whiff of a constitutional stink.

Comments are closed